The July/August 2019 issue of Zymurgy included a clone recipe of Tree Houses’ Julius. The recipe author included a dry yeast blend that is possibly used by the brewers themselves and is apparently responsible for providing the beer with a lot of it’s character. Seeing how I work at a yeast lab, I had access to some tools I could use to determine what yeast is in a can of Julius. It was also a great chance for me to get more experience with DNA extraction and PCR!

Isolation

During a recent trip to Rhode Island my partner and I stopped at Tree House to see what all the hype was about (psst, their Pilsner game is on point!) where we obtained some cans of Julius; among other things. The product was kept as cold as possible until I could get back to the lab. Most of the beer was aseptically shared so we could rouse whatever yeast had flocculated to the bottom of the can. This is the yeast sample we would be streaking to determine what strains are actually in the can.

To make it easier to isolate different yeast strains we use an agar media called Wallerstein Lab Nutrient (WLN). This media contains a dye which some yeast will take up. Some strains may look a deep green while others may take up very little and still look white. This differential media makes it easier to determine if a culture is pure or not. For quality control purposes this can help one determine if a contamination has been picked up. From an isolation standpoint it makes it easier to select each separate strain and re-plate them for further analysis.

The first streak plate came back with a very obvious mixed culture and over a couple subsequent isolation steps I had what appeared to be four different strains. The media we use also contains Ferulic Acid so we can perform some sensory evaluation to determine if a yeast is Phenolic Off-Flavour positive (POF+). One of the yeasts isolated had a very strong clove aroma coming off the plate.

Testing the Clone Yeast

The yeast strains listed in the Zymurgy recipe are: S-04, WB-06 and T-58. We acquired some pitches of dry yeast to also plate so we could have something to compare the can isolates with. A combination of these yeast seems to be commonly believed to be what is used by Tree House for their core product.

Considering how heavily hopped their beers are; using dry yeast is possibly the most economical approach. The beers are hopped before yeast even has a chance to settle out, resulting in a yeast culture that would be hard if not impossible to work with. There’s also the risk for drift if the product is used as a blend from the first generation on.

DNA Extraction and Validation

The extraction on it’s own is fairly straightforward. We use this product called “Instagene Matrix” that makes it very easy to break open the yeast and expose their DNA. This solution has a yeast colony added to it then undergoes a few heating steps to break open the cells. At this point we are “done” doing our extraction, however it doesn’t always work on the first try so we always want to validate that the DNA extraction worked.

We use Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) on a sample of the extracted DNA to ensure that our process works. I’m a computer scientist, so I don’t know all the ins and outs of PCR, but it basically works by having a primer that hooks up to a target piece of DNA. DNA follow certain rules and during one of the reactions it builds out the strand. PCR is a “chain reaction” because it is an exponential process. For example, with 1 piece of target DNA we would create 2 on the first iteration, 4 on the second iteration and if we were to repeat this process 30 times we’d have 1,073,741,824 bits of DNA kicking around!

Since all we are doing is checking to see that the DNA was properly extracted we use a primer that basically all yeast strains contain, the ITS primer. This primer is used along with a “Master Mix” that contains a bunch of other necessary components for PCR to actually work. Once everything has been prepared it’s loaded into a Thermocycler and does it’s magic for about 3 hours. After the process is done the product is loaded into a gel to see if everything worked. If it does you end up with something that looks like this.

PCR is a bit of a heart breaker and in some cases you’ll end up with nothing. Sometimes that’s a good thing, such as using PCR to detect diastatic yeast where you don’t want any. However, if you were trying to amplify something and it didn’t work, you go cry in a corner because you just wasted 8 hours of your life and have nothing to show for it. When doing research at the masters or doctoral level this can happen over and over again for months!

DNA Fingerprinting

The final step to determine if there’s any shared yeasts between the dry products and those yeasts found in the beer is to run the DNA through a fingerprinting step. Fingerprinting is a useful tool to determine if something shares similar DNA, which can be useful to determine if two yeasts are the same. The results of fingerprinting look like a DNA test that you might have seen on a crime show.

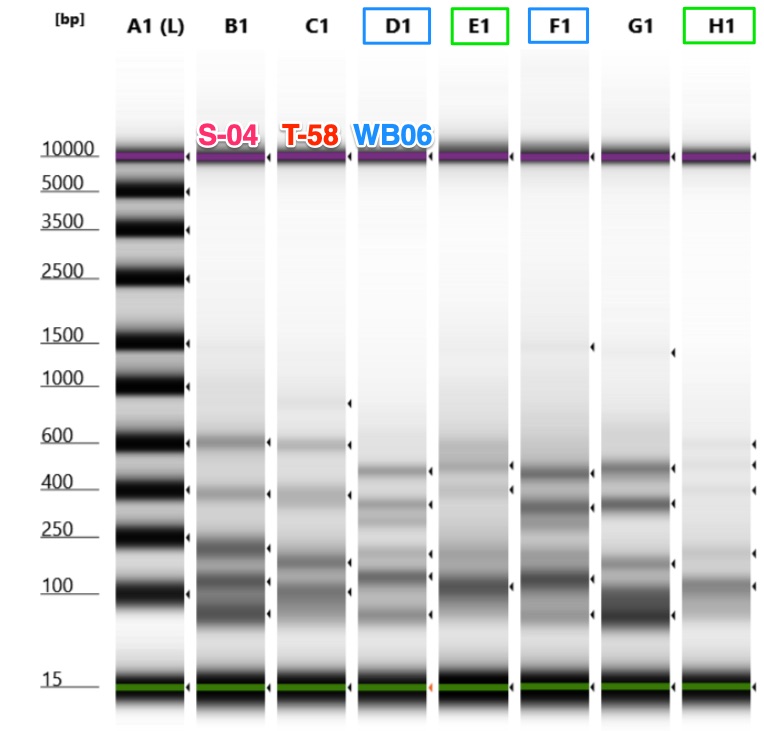

The fingerprinting performed is called “interdelta fingerprinting” and used the delta 12 and delta 21 primers which was then run on a digital capillary electrophoresis unit. See Legras and Karst (2003) for more details about this method.

Results

Looking at the resulting bands we can see a very strong similarity between lanes D1 and F1. There’s some slightly different intensities but the lines are pretty similar. The colony from this plate was also POF+ so it seems that it’s quite likely that WB-06 is one of the strains used by Tree House.

Comparing our known sources (lanes B1 and C1) there don’t appear to be any other matches with the strains purported to be part of the Tree House house culture. However, E1 and H1 do match which means that what I thought were different yeasts (based on morphology) are quite likely the same. One thing that is interesting though is there appear to be three separate yeast strains in a can of Julius!

From what I was able to see from my plating there are three unique strains in their yeast blend as well, but they don’t appear to be S-04 or T-58. However, based on the results there does indeed seem to be WB-06 in the mixed culture. It’s possible that wheat strains are good at biotransformation, which might be why it is being included. As for the other two strains, there’s other dry yeasts on the market that could be tested to determine what makes up Tree House’s secret sauce. For now though, I think I might just grow these yeasts up from colony and see what kinds of beer they make on their own 😉

Additional Resources

Polymerase Chain Reaction

- http://suigenerisbrewing.com/index.php/2017/11/22/contamination-detection-1/

- http://suigenerisbrewing.com/index.php/2017/11/24/contamination-detection-2/

Plating and Isolation Techniques

- http://suigenerisbrewing.com/index.php/2014/08/09/your-home-yeast-lab-made-easy-streak-plates/

- http://suigenerisbrewing.com/index.php/2015/05/08/purifying-yeast-from-infected-cultures-part-2/

- https://www.escarpmentlabs.com/single-post/2019/03/18/agar-plating-guide

- http://www.milkthefunk.com/wiki/Laboratory_Techniques#Techniques

This was a fun read! It’s been a good long time since I’ve seen anyone try to make any progress figuring out what’s in Julius. Thanks for taking the time to do this. I’m curious what may come from it.

LikeLike

If you can get the DNA of your colonies into an Illumina or other sequencer, it’d be possible to run a genetic tree/comparison to plenty of other dry yeast strains using the short read data.

I reckon Nottingham and Munich might be worth looking at, also the Lallemand NEIPA, maybe they switched from S-04 at some point

LikeLike

Have you ever plated another highly hopped unfiltered beer that isn’t tree house? I’m extremely skeptical of the claims that they are using multiple yeast strains given their production size and their obsession with consistency. To use multiple yeasts make little to no sense from a production brewery’s standpoint given the inevitably of generational drift. Breweries of that size and actually most all sizes, harvest and repitch their house yeast for many generations because It’s more financially and economically sensible for them to do so, to purchase fresh yeast with every new pitch would not be a wise move from a business standpoint and after the end of the day a brewery is a business first.

It seems more plausible that the other “yeast” you claim to have identified are introduced unintentionally via other means such as from the immense dry hopping regime they employ, maybe all the hop oils and yeast bio transformation of said hop oils are slowly mutating the underlying base yeast strain. Also another possible mutations from subsequent generations of repitching their house yeast strain.

I’d be curious the results of these same tests done on another extremely hopped unfiltered beer such a heady topper for example.

LikeLike

> I’m extremely skeptical of the claims that they are using multiple yeast strains given their production size and their obsession with consistency.

At the levels of dry-hopping they are doing, repitching the same yeast over and over can end up being pretty hard. Their hopping schedules aren’t conducive to harvesting, so you are running the risk of pulling off yeast too early or pulling crashed yeast that is full of hops.

In terms of costs dry yeast is extremely economical and if it’s a yeast blend very easy to do at their scale. They are working with very large tanks (at least 100hL), and at that level it becomes easy to do “yeast math” for blends. A 500g pack of dry yeast is good for about 5hL and at a 100hL batch size would require about 20 packs of yeast. The ratio could be something like 18 packs S-04, 1 T-58 and 1 WB-06. Sure, it’s probably $1200 – $1600 for the yeast, but it’s easy to do. Something to also remember is they don’t need to worry about the product moving, because it will. It’s also a pretty expensive product.

Regarding your comments about contamination being introduced from dry hopping; while that is possible I’d find it highly convenient that the contaminant appears to be genetically similar to WB-06. If TreeHouse were to be making lots of other styles of beers (such as Hefeweizens) then a contamination due to improper cleaning techniques could help explain how other yeast is getting introduced into the finished product (such as from a packaging line). As for genetic drift, breweries aren’t using the same yeast for long enough to see that kind of stuff happen. In these kinds of situations it’s usually best to apply Occams Razor, the simplest answer is probably the right one.

LikeLike

Awesome work! Any luck brewing with the isolates? Any idea what the other yeast might be and how they are used yet? I also read that there was a brewery in the U.K. who analyzed a Julius can and found Belgian yeast in it. Wonder what their other findings were.

LikeLike

So E1 and G1 remain unidentified…any chance you’ll be testing more Safale yeasts? Thanks for this.

LikeLike

Did you bother stepping up these 3 strains and fermenting out beer with them individually? Also, are you tempted to get a hold of a whole bunch of dry yeasts to add to your gel comparisons? It would be great to see and read such meanderings.

LikeLike

FYI someone also found S-04 in Julius:

https://www.homebrewtalk.com/threads/isolated-yeast-tree-house-how-to-identify-and-characterize.623221/page-90#post-8927461

LikeLike